When I was a child I had a cactus of great stature that was placed on the window board of my room. I loved this prickly plant. Funnily enough, I thought it was the prettiest thing I had ever seen, and I often looked at it in broad daylight without the slightest fear or suspicion. It was a cactus. Nothing more. Nothing less.

But I was four years old at that time and as such rife with groundless anxieties that rose as soon as the sun set. Ghosts lived under my bed, witches in my wardrobe and ugly little goblins in my doll house. In an attempt to secure my nighttime peace, I negotiated a comprehensive code of conduct with the spirits that I believed to haunt the house. Every night I had to execute one and the same routine to make sure they weren't allowed to leave their hiding place to attack me during my sleep. It was a fairly arduous choreography that had to be completed without a mistake but once I managed to make it, I thought myself safe.

Until the day when the species of wolves entered the circle of my enemies. For one reason or another, I developed a sheer terror of these quadrupeds although my parents repeatedly promised that they had long left Bavaria to move to the neighbouring countries in the East. There is no need to mention that my parents' pledge wasn't worth a penny at night. The absence of daylight turns every children's room into a projection surface for infantile phantasies and horrors, and my imagination was as vivid as my courage was absent.

In this particular case, a wolf had settled behind the rifle-green roller blind that my parents lowered in the evening before they sent me to bed. The predator appeared as the shadow of a big wolfish head that looked so terrifying that it either deprived me of sleep or gave me horrid nightmares. This went on for a couple of months - although the childish awareness of time can be misleading here - until one day a true miracle happened. The wolf head underwent a wondrous metamorphosis and turned into a horse - an animal that I was devoted to with great affection.

I believe, it is the fear that explains why the existence of a wolf on my window board hadn't aroused any suspicion, whereas the horse head did. I looked into the matter with a first sprout of ratio and finally mustered up the courage to look behind the blinds as soon as I was sure that the horse wouldn't turn back to its wolfish state.

Today, I can't remember if I was surprised or happy to find out that it was the cactus who staged a nocturnal shadow play, and that the wolf had transformed into a horse because my mum had turned the cactus around to make sure it wouldn't lean towards the sun whilst growing.

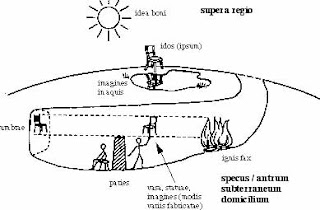

Years later, I was reminded of this incidence of enlightenment during a philosophy class. The subject was Plato's "Allegory of the Cave" that is part of "The Republic" and, very briefly, draws on the image of objects and their shadows to examine how the human perception and denomination of matters is subject to education.

Today, I was thinking about the allegory and enlightenment in general as sometimes I find it rather boring to live in the undeceived age of education that offers scientific answers to most or let's be honest almost all of my everyday questions.

How astonishing it must have been when mankind found out that the world wasn't flat. Sometimes, I would prefer the company of questions marks and could easily do without the opportunity to turn each query into a solution by combing through the sheer infinite pool of knowledge that is out there. All I have to do is browse the books, the web and it won't take long before I am presented with one crystal clear fact or several methods of resolutions that I can then examine and apply to my liking. Wouldn't it be nice to not know things for a change? Wouldn't it be nice to be clueless and unillumined sometimes? Wouldn't it be nice to have access to the cave of ignorance? If you have the key, please get in touch.

"Any one who has common sense will remember that the bewilderments of the eyes are two kinds, and arise from two causes, either from coming out of the light or from going into the light, which is true of the mind's eye, quite as much as of the bodily eye, and he who remembers this when he sees any one whose vision is perplexed and weak, will not be too ready to laugh, he will first ask whether that soul of man has come out of the brighter light, and is unable to see because unaccustomed to the dark, or having turned from darkness to the day is dazzled by excess of light. And he will count the one happy in his condition and state of being, and he will pity the other; or, if he have a mind to laugh at the soul which comes from below into the light, there will be more reason in this than in the laugh which greets him who returns from above out of the light into the cave." ~ Plato, The Republic